Plato’s Republic

Welcome to my new series. Humans are unique creatures because we attain the knowledge of our own existence. We inhabit the tools to think which allow us to reshape our own lives for the better, from the individual to society at large. We use our minds to make sense of the world around us. Broadly speaking, our perceptions and understanding of objective reality hinge on 3 pillars.

- First there is science, that which we know to be true because it is proved.

- The opposite pillar stands religion, truth told through story. This pillar offers a moral guide, principals, ethics to which we adhere so we may live in peace and harmony with our fellow man. It teaches us to hold our inner demons at bay.

- The third pillar, the metaphysical, or the philosophical exists where the hard facts of science blend with the mystical and the unexplained components of the spiritual.

Across the plains of time the greatest minds employed philosophy as a means to penetrate life’s deepest mysteries and to shape our role in the universe. Why can we think? Why are we the only beings aware of our fleeting existence? Do our lived experiences matter to the universe? Why is it in our nature to congregate in a shared space, to develop governments, methods of rule where we permit some of us to assume power, wealth, and status. For thousands of years the brightest among us toiled with these eternal questions in an effort to extract meaning from the universe. A practice that is just as relevant today.

History’s greatest thinkers have profoundly shaped our modern world, perhaps in ways we still don’t fully understand. It’s these ideas from these great individuals that I wish to explore and share with you.

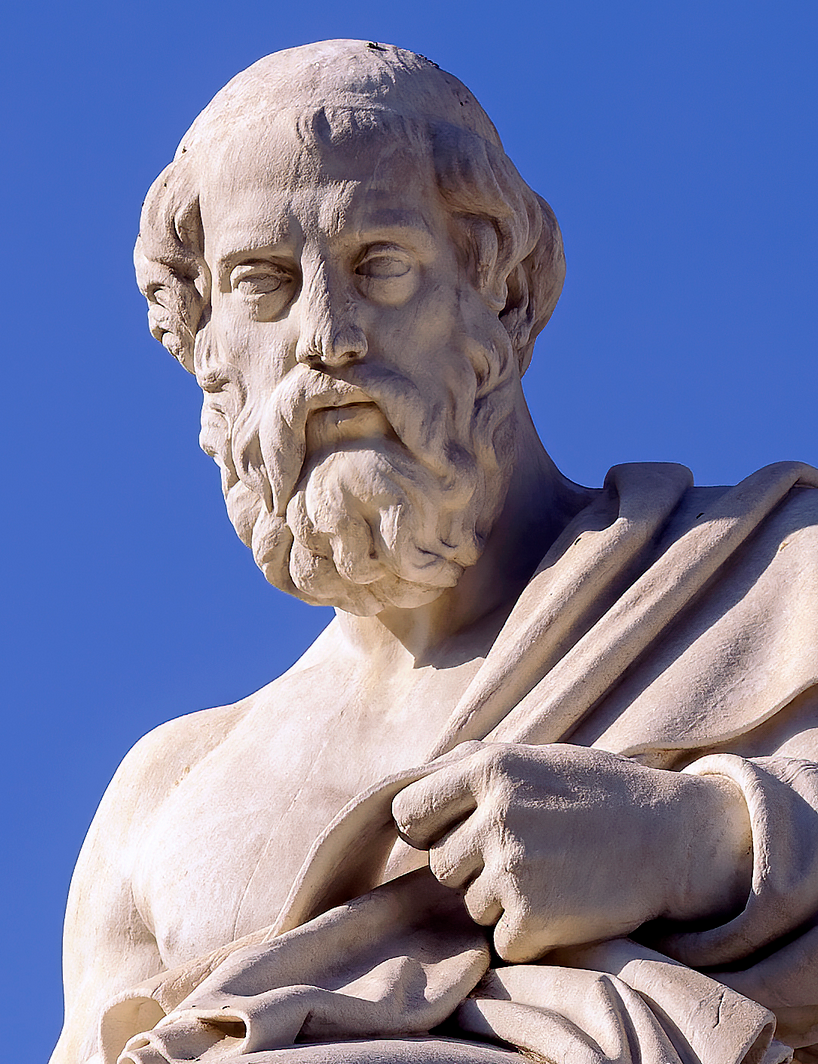

Let’s begin with Plato (427 – 348 BC)

Who Was Plato?

Plato honed his thinking muscles under the guidance of the famed Socrates. We revere Socrates and his legendary Socratic Method but the man known for pushing individuals to challenge their belief system wasn’t exactly loved during his life. We will discuss the tragic end of Socrates later, as it largely defined Plato’s future.

Plato’s most significant achievement is The Republic, a book mapping out his ideas in the form of characters sharing dialogue. This is where his most iconic theories on developing a perfect society, or utopia may be found. It’s in this famous literary achievement where he ponders 2 simple questions…

1. What is justice? How does one build a just society?

2. Is Utopia achievable? In other words, can we craft a system of government where power resides only among the best and brightest and kept away from the dithering hands of the corrupt and incompetent?

His answers to these questions are extrapolated from decades of exploration, research, observance, and wisdom gained. His conclusions…

1. Utopia is achievable

2. Democracy is not the answer

For those of us living in a democratic nation, we might be aghast upon reading that 2nd point. It’s an odd thing to hear given that “Democracy” is the government structure that defines the west. It’s the system of rule that we associate with untrammeled freedom to the individual, whose very roots are traced to Greece itself.

Where does his detestation for the notion that “power is best when shared among the many” originate? As it turns out, the very place that revolutionized democracy, Athens itself.

The War that Broke Athens

The catastrophic conflict between Athens and Sparta, the Peloponnesian War, defined Plato’s early life. The 2 rival states battles on and off for 30 years. The scale of the conflict spread and consumed all of Greece. All polis, or city states, were forced to participate. After decades of turbulent, relentless combat economic depression, starvation, and plague settled in and ravaged the country side and wiping out vast swaths of the population.

In the end, Athens lost. The Spartan army march through the city, to the great embarrassment and shame of city dwellers. They occupied it for a brief span and then returned home. Outraged and livid, Athenians couldn’t believe what they experienced. Unlike Sparta, Athens was home to tremendous wealth. It was a bastion of Hellenistic culture, boasting supremacy amid all Greek states in the arts, sciences, music, and theater. Athens had the Mediterranean’s strongest navy, and largest economy by far. The inhabitants viewed Athens as a true city upon a hill. Imagine if the much poorer and less capable South defeated the North in the American Civil War and waltzed through the nation’s capital. Northern fury would know no bounds.

How then did Athens lose? Socrates argued that democracy was to blame.

Athenian Democracy: It’s Not Like Ours

Athens did not invent democracy, but it was the first city state to adopt the most liberal form of democracy in the ancient world. To grossly oversimplify, Athenian citizens lived under a direct democracy, which meant voters didn’t just vote on policies but were able to participate in and draft all forms of government legislation ranging from criminal justice, to the economy, to warfare. Your average, everyday citizens met once a month in an assembly to vote on, and pass laws.

This differs heavily from our U.S. Democratic Republic where people vote for electors, who in turn elect our politicians who do that boring stuff for us. In Athens, the right to vote was granted only to male citizens, no women or slaves need apply.

After the Spartans humiliated Athens, a fuming Socrates wasted no time blaming the democrats. Democracy, he argued, made the process of lawmaking too cumbersome. The city should never have allowed so many unqualified degenerates to vote on crucial military matters in the midst of a large scale war. He characterized the system as incompetent, slow, and frustrating. Socrates believed that the communal sharing of power resulted in one too many idiots stifled the few sophisticated citizens from lead Athens to victory. The defeat, simply put, was the fault of the weak and uneducated masses.

Socrates Dies, Plato Enters the World

Socrates was far from the only citizen who shared “unsavory” views of the democratic system. Shortly after the war, the aristocracy launched a coup against the democrats. The revolution failed. And Socrates, who was the loudest and most public supporter of the failed usurpers was sentenced to death. The governing body did first allow Socrates to flee, but the master refused. He was going to stay, and make the governing body follow through with his execution. This is something democrats had quietly hoped to avoid. Their power rested on fragile support. And Socrates was beloved. Killing the city’s biggest celebrity over a conflict of visions would discredit their legitimacy. And future generations would praise Socrates as a martyr.

They sentence him to death anyway. Socrates perishes, a sight beheld by his weeping students and followers. Plato among them. Shortly after Socrates breathed his last, Plato fled from Athens as he too supported the failed revolution. In 399 BC the 28-year-old prodigy, absconds from Greece and travels abroad.

The youth spends 12 years venturing across the eastern Mediterranean. A wondering vagabond in search of meaning. His feet brought him to Egypt, Syracuse, Italy, and Cyrene. In 387 BC, Plato returns to Greece, now a master of the arts, as well as thought. He establishes his own school of philosophy. He publishes his theories across many dialogues. But it’s his greatest achievement The Republic that stands apart as his greatest accomplishment.

The Republic

Socrates death bore tremendous influence over Plato’s view of government. Plato embraced the notion that power must dwell only among the strongest and wisest men. The concept echos similar Great Man theories touted by future philosophers such as Nietzsche and Rand. Let’s explore Plato’s attempt to navigate the confounded state of man’s role in society.

The Ethical Problem

According to Plato, the heart of ethics lies this question, what is justice? Here Plato grapples with the contemporary views of justice held by his peers, that might makes right. Athens for example had the power to coerce its weaker neighbors to join their war against Sparta. Their neighbors had no choice but to pledge obeisance to avoid dealing with the wrath of a much stronger enemy.

But was this justice? Is it better to be strong or to be good? Should those qualities be at odds or can they coexist? Plato wasn’t sure. He determined that justice varied in meaning and degree when meted out between societies and individuals. He believed that for the common man to be just, he must extoll courage and intelligence.

Plato argued that justice was more difficult to define among individuals, and easer to determine at the macro level. He did believe that justice is the natural outgrowth of healthy, whole relationships built between individuals. The strength of bonds at the individual level will act as a firm base though which communities at large can flourish.

The Political Problem

Men are not happy to live a simple life, they hunger for adventure Plato surmises. He correctly believed that governments will crumble from too much excess. If the governing body doesn’t keep itself in check, the next organic step is revolution beset by the irascible masses. Once the people wrestle power from the ruling class they will distribute it among themselves, forming the democratic structure. This too ends with more excess as power and wealth will find its way to one person or a group who persuades the fickle citizens to lift them up via referendum. Plato believed autocrats ascend by telling the people what they wish to hear. Over time the elected officials who reap the benefits of their swindling capabilities will eventually over indulge and drown in extravagance. The execrable cycle will forever repeat itself. Plato was convinced that the people will always vote for the person who appeals to their appetite in lieu of the person most competent to lead. So how do we deliver the reigns of power into the right hands?

Plate advocated for what he called “The Philosopher King.” That refers to the man (or group) who prioritizes the quest for knowledge over satisfying his primal desires. Even though King suggests a singular person, Plato preferred instead a small group of society’s wisest and most capable men to rule. To many this might sound like an Oligarchicy. But his vision is more complicated. This group of leaders will not simply be handed government titles. They will earn it through decades of trial. I will summarize in 9 steps what this process entails…

1. Children will be herded — or kindly placed* — into a state sponsored academy. They must begin young so the counselors can thwart the influence of their parents.

2. Between the ages of 10 – 20, the kiddos will undergo mostly physical, bodily education (intense workouts, constant exorcise.)

3. But they will also master instruments for psychological gain. And they will be taught to embrace religion. Plato posited that a God worshiping society will generate shared and common values. Whereas A Godless society will produce contrasting moral principles and division that will tear the community fabric to pieces.

4. At age 20, the young adults will engage in a series of tests. Those who fail will be eliminated. And to prevent the ousted from growing angry and resentful, Plato will instill in them the idea that missing the cut was part of God’s just plan.

5. Another 10 years of training awaits the chosen who made it.

6. At 30, they will go through another culling.

7. From 30 – 35, the lucky few remaining will learn what Plato considered to be the highest form of philosophy, mathematics.

8. Once they hit the age of 35, they will undergo their biggest test yet. 15 years of putting everything they learned into practice. They must venture forth into the world and build, create, innovate and measure the results. Their knowledge will enter a real-life trial and error simulation.

9. The top echelon that survives this test will become the rulers of the state at age 50. They will hold no private property. They will not be wealthy, and they will be forced to live in a shared commune. They will not have access to the common excesses that often tempt the powerful.

The Solution

According to Plato, this is the proper vehicle to build a perfect society. The system is fair, as anyone who wants to hold office can try the academy. The playing field is equal for all, and participation is closed to no one (except women and slaves.) There will be no votes, no special favors, no bribes, and no nepotism. It doesn’t matter if you herald from a family of royalty or a wealthy general, or if you were birthed in poverty.

And the trials of the academy will instill enough virtue into the magnificent few that they will not be tempted self-indulge. They will not become corrupted or despotic. The decades of experience and wisdom they attain will always serve as their guide.

Does This Work?

At first thought the entire idea presented might sound ridiculous and far too unrealistic to ever be put in practice. However, some historians have pointed to real places where Plato’s vision manifested, at least to a degree. The clergy in the Catholic Church who reigned over medieval Europe is one example. American historian Will Durant also referred to the priests who ruled Egypt and the commune in Sicily, both places Plato had traveled to and witnessed first hand as examples of places where systems are in place to ensure the most qualified rule.

However, I don’t believe that adapting his model society verbatim would ever live up to the entropic and messy nature of reality. If it takes 50 years to reel in the new generation of leaders then what happens when emergency strikes? How would the academy cope when a hostile nation unleashes its armies into your city? How would this decades-long process weather the pandemonium caused by economic strife, or the sudden onslaught of plague, or a cataclysmic natural event? In those scenarios when real panic hits that community I believe the academy will be suspended, and then those out of power will take advantage of the crisis by siphoning the reigns from those distracted leaders.

The other issue is that those eliminated from the academy will not stand idly and accept their failure as God’s will. There will be resentment. There will be jealousy and anger among those who don’t make it to the next round. I could easily envision a revolution, or something that looks like civil war erupting between the chosen and the fallen. And there will be many more people on the outside looking in than people in the academy looking out. The numbers game here does not work in the academy’s favor.

And last, even though the rulers in charge won’t be granted wealth and luxury, the allure of power will always draw those on the outside to circumvent the academy and find a way to infiltrate. Bribery, scandal, and conspiracy will permeate, and then corrupt the system.

The United States’ founding fathers introduced a much more efficient system of government. Instead of ensuring that the “best” rule, our revolutionaries drafted a constitution where power is lodged into a web of competing interests pushing and pulling against the other. We have the commander in chief, who can’t pass laws without the approval of the legislature. The legislature cannot draft and approve bills unless the judiciary determines that it is lawful. The 3 branches of our federal government play a continuous game of tug-of-war. And then there is the other game of tug-of-war over competing interests between DC and state and local governing bodies. This constant, back-and-forth struggle was an ingenious invention by our nation’s founders because while we compete for power and our own self-interest, the Constitution guarantees us our civil liberties so that we also have the freedom to paint our own life journey.

To paraphrase the great Dr. Thomas Sowell, “the smartest 1% among us don’t know half of everything, they don’t even know 1/10th of everything.”

Up next: Aristotle

Excellent! Very interesting and insightful!

Thank you for reading!

Your brief history and analysis of Plato’s ideas is very well-written. well-written.

Plato’s notion is an interesting, yet as you pointed out, a flawed one. Human beings are a curious lot; they embody the absolute worst and cruelest aspects of man as well as his loftiest and most unselfish aspects. But the most basic of requirements for man is his instinct to survive, which in a larger sense means fulfilling his own self-interest.

I do believe though, that there are certain callings that supersede his self interest such as love of one’s children and partner and in some cases religious ideas and love of country. But, I do not believe that man has evolved spiritually to any great extent, from the time of Plato, making his ideas of the “ideal” government highly impractical.

Thank you for your analysis!

Comments are closed.